An Irish blessing:

Family, students create Celtic cross to remember a youth’s life

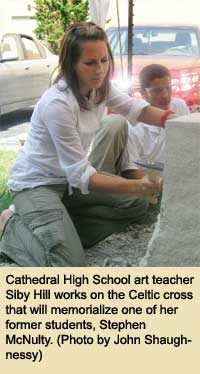

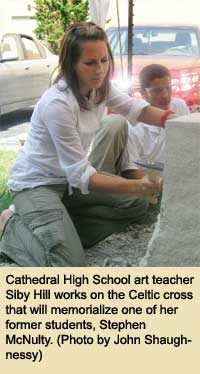

By John Shaughnessy

She knew it would be the trip of a lifetime, a journey to Ireland and Scotland that would help her show her students the beauty and mystery of art and faith.

She knew it would be the trip of a lifetime, a journey to Ireland and Scotland that would help her show her students the beauty and mystery of art and faith.

So when Siby Hill received a Teacher Creativity grant from Lilly Endowment in Indianapolis this year, she immediately made plans to study the Celtic crosses and other stone carvings that have captivated her for years—the crosses and carvings that have dotted the landscapes of Ireland and Scotland for at least

15 centuries.

With her $8,000 grant, Hill even secretly dreamed of having her students at Cathedral High School in Indianapolis eventually create a Celtic cross. The

26-year-old art teacher believed a Celtic cross would be a natural addition for a Catholic school with the nickname “Irish.”

After all, for Irish Catholics, the Celtic cross is a symbol that blends faith, heritage and the belief in

eternity.

Yet amid the excitement and joy of her plans came devastating news just nine days after St. Patrick’s Day. One of her art students had died unexpectedly.

The news rocked Hill and soon led her on a different journey—a journey that would bring her closer to the family of the student, a journey that would lead the

family from the depths of heartbreak to the hope of healing, a journey that would show all of them the beauty and mystery of life and faith.

‘God brought us all together’

When Hill learned that Stephen McNulty died on March 26, the news devastated her. She immediately thought of how the 18-year-old senior at Cathedral shared her passion for art.

“Stephen just had so much excitement for art in

general,” she recalls. “It made me think I could work with him some more. We built a relationship off of that. Not a lot of students are passionate about art. He became a good friend.”

Before his death, Stephen had been making an

18-inch-high house in Hill’s ceramics and sculpture class. Two weeks after his funeral, Hill put the finishing touches on the house and gave it to Stephen’s mother in her classroom.

Touched by the gift, Jacque McNulty told Hill that she and her husband, Jerry, wanted to create a Celtic cross in Stephen’s memory. That hope stunned Hill.

She wanted to tell Jacque about her desire to have her students make a Celtic cross after she returned from Ireland and Scotland, but she resisted. She didn’t know Stephen’s parents very well, and she wanted to talk to Cathedral administrators first about the idea of

combining the two goals.

“That night, I felt a peace come over me,” Hill recalls as she stands beneath the white tent on the Cathedral campus where the Celtic cross is being created from stone. “Everyone I talked to at Cathedral said it was a good idea. God brought us all together.”

“As he continues to do,” Jacque says, standing near Hill. “We welcomed it and embraced it, as a blessing.”

In early June, Hill traveled to Ireland and Scotland to study the Celtic crosses and other stone carvings.

“I was there for 10 days,” she recalls. “I focused primarily on St. Martin’s cross on the Isle of Iona on the west coast of Scotland. The stone was commissioned by Irish monks and served as a monument to the great St. Martin. Our Celtic cross is patterned after that one. All the time I was there, I had Stephen and the McNultys on my mind.”

When Hill returned, she enrolled in a stone carving class at the Indianapolis Art Center. Learning of her goal to create the Celtic cross, center officials donated two huge slabs of limestone for the project: a 9-foot-long, 5,000-pound slab for the cross and a 3-foot-high, 2,800-pound slab for the base of the cross. Workers for the Shiel Sexton Co. moved the slabs to Cathedral’s campus. By early July, the project was ready to begin.

Etched in a mother’s heart

There’s a photo of Jacque McNulty using an industrial-sized drill to cut into the limestone slab that’s destined to be the Celtic cross that memorializes Stephen.

In the photo, the legs and arms of the 5-foot, 4-inch woman are taut as she bears down on the stone on a hot summer day, sweat flowing from her body.

“No matter how hot it got, no matter how much I sweated, I loved every part of it,” Jacque recalls. “I got up there and the drill is so big. You have to put so much pressure on the drill. And hold it as tightly as you could. It was the hardest thing I ever did.”

As she recalls those July days, Jacque sits at the head of the limestone cross. She caresses the stone softly, just as a mother would caress the head of a sick child in bed.

“We were very close,” she says about Stephen. “We shared a lot. He was a hugger, a lover. The relationship we had was awesome. I miss him.

“The doctor said he died because of a weakening of the muscles around his heart. We had no [warning] signs for Stephen. He wasn’t sick. He went to school that Friday and died on that Sunday. He came home, gave me a hug and told me he loved me. Jerry found him in bed the next morning.”

She still pictures him on the last day of his senior retreat at Cathedral.

“Two weeks before he died, he wrote a letter to me and he told me he was grateful to me for pushing him to go on his spiritual journey,” she says. “At the closing, Stephen led the whole retreat group out. He was crying. He felt he had a whole new understanding of his spiritual side.”

She touches the stone again.

“The name of the cross will be Legacy,” she says. “He loved art, he loved Ireland, he loved his heritage. This makes me proud because it’s for my son. And it’s humbling seeing all the kids who have been involved in this.

“Working on it has helped in my healing process for my son. It’s just been a great experience for me. It makes me feel close to him.”

The bond of brothers

Ismaila “Izo” Ndiaye instructs the students who have signed up for the sculpture class at Cathedral to create the Celtic cross.

An Indianapolis artist and stone carver who is originally from Senegal, West Africa, Ndiaye knows that when the drilling and the carving of the stone is being done correctly, there is a certain sound—even a musical quality—that can be heard.

Everything was in harmony when Hill told Ndiaye about the Celtic cross project and asked the Indianapolis Art Center instructor to work with her students.

“This is the first time I’ve done a memorial,” he says. “For this, I’ll give more than 100 percent to make the family happy. I know it’s very hard to have this loss. As long as we see this, he’s still around us. He’s still with us.”

Stephen’s younger brother, Patrick, is one of the students in the sculpture class. At 16, Patrick has also been working on the Celtic cross since early July.

“My dad came to me and said, ‘I need help for two days,’ ” Patrick recalls. “Those two days turned into three-and-a-half weeks. I had help from my friends.”

The friends who helped came from Cathedral, Roncalli High School, Father Thomas Scecina Memorial High School and Heritage Christian High School, all in Indianapolis.

The sweat poured from them as they drilled and carved the stone for long hours in the furnace heat of July.

“It’s really neat how they’ve all pulled together,” says Jerry McNulty, whose family belongs to Holy Spirit Parish in Indianapolis. “At Stephen’s funeral, there were kids from just about all the Catholic high schools. To see them come together like that, you just remember why you send your kids to these schools—especially when you see them go to the roots of their faith.”

Patrick remembers finding the roots of his relationship with Stephen. The connection came even as their interests differed. Patrick loves sports. Stephen loved the arts. The bond of brothers still led them to embrace each other, especially during the years when they were the only McNulty children still living at home.

“Me and him are completely opposite people, but the last two years it was great,” Patrick recalls as he stands by the cross. “I figured him out. We connected on a lot of things. I call him my best friend. We talked an hour every night, no matter what time he came home.”

His brother’s voice stayed with Patrick as he worked on the cross during the summer.

“Sometimes I would laugh because I knew he was laughing at me for doing all this work for him,” Patrick says, smiling. “At times, it was tiring. At times, it was stressful. At times, it was peaceful. It means a lot to me because it’s for my brother.”

A family’s greatest challenge

One of the memories that the McNulty family cherishes is a trip to Ireland in 2005.

The McNulty’s two older children—Kristin, 25, and Brad, 23—were also part of that trip with Stephen, Patrick, Jacque and Jerry. So was Kristin’s husband, Jason McClellan.

“My grandfather came over from Ireland in 1917,” Jerry says. “We still have family there in Kilcar in County Donegal. My grandfather took my father to Ireland. My father took me. I decided to take my kids. Stephen really learned a lot about his Irish heritage on the trip.”

“It was such a gift,” Jacque says. “It was a blessing we all went.”

The family has continued to call on those gifts and blessings of life as they still struggle with Stephen’s death.

“The first thing I realized is that it puts a heavy load on the family,” Jerry says. “From other people’s experiences, I know it can tear a family apart. We’ve tried to address the issues right away to save the family.”

As the family has been tested, the McNultys have

also recognized the support and love of their extended family—from Cathedral to the larger Catholic community.

We’ve gotten a lot of support from friends,” Jerry says. “And Father [Glenn] O’Connor, Father [Joseph] Riedman and Father [William] Munshower have been extremely helpful.”

The McNultys have treasured and relied on that larger family just as they’ve treasured and relied on being involved in creating the Celtic cross.

The cross is expected to be finished by the end of September. A dedication—unscheduled at this time—is planned for some time in October.

“I’ll be in awe to see it standing,” Hill says. “I’ll be in awe of the power the Celtic cross conveys and the feeling it gives. It moves you.”

She pauses and glances at the cross that’s being created by the efforts of her students, and by the love of Stephen’s family.

“When we reach out and touch that cross,” she says, “it will have a story.” †