A good death: End-of-life issues complicated by faith, technology, family concerns

By John Shaughnessy

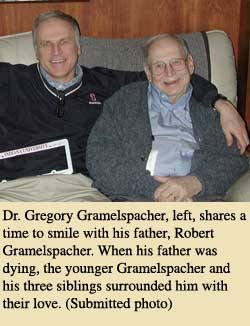

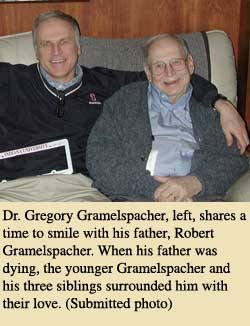

Before his father’s death, Dr. Gregory Gramelspacher fed him his last meal, spooning him tastes of orange sherbet.

Before his father’s death, Dr. Gregory Gramelspacher fed him his last meal, spooning him tastes of orange sherbet.

Later, the 52-year-old physician climbed into the bed of his 81-year-old father, holding him and cupping his jaw to help quiet his labored breathing.

And when he knew his father was about to die, just before 3 a.m., the son woke his three siblings so they could say their goodbyes to their father, too.

“There is something sacred about life, coming into the world and leaving the world,” said Gramelspacher, a member of St. Luke Parish in Indianapolis. “I felt that way when my Dad died.”

Even before his father’s passing this year, Gramelspacher has long been an advocate for what he considers “a good death,” the kind where a person gets to die peacefully and relatively pain-free, preferably surrounded by friends and family at home.

Like many Catholics and other Americans, Gramelspacher also knows the subject of death-with-dignity is an ever-growing concern in the United States, especially in an era when faith, family dynamics and modern technology often collide, creating challenging ethical questions about the right course of action for patients, families and doctors.

The Church offers its own guidance concerning end-of-life ethical issues.

“Life is a basic good but not an absolute good,” said Father Joseph Rautenberg, the consultant on ethics and bioethics for the Archdiocese of Indianapolis. “Two principles come out of that: You can never intentionally kill, but you don’t have to preserve life at all costs.”

Father Rautenberg offered that insight when he and Gramelspacher spoke recently at St. Thomas Aquinas Parish in Indianapolis on the topic “Bioethical Dilemmas at the End of Life.”

The priest stressed two key points among the directives that the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops issued concerning care for the dying:

• A person has a moral obligation to use ordinary or proportionate means of preserving his or her life. Proportionate means are those that in the judgment of the patient offer a reasonable hope of benefit and do not entail an excessive burden or impose excessive expense on the family or the community.

• A person may forgo extraordinary or disproportionate means of preserving life.

“The bishops want you to look at the burdens and the benefits to the patient, especially in light of the patient’s wishes,” Father Rautenberg said.

End–of-life issues are a constant—and often complex—concern for everyone involved, according to Father John Mannion, the head of the institutional ethics committee at St. Francis Hospital and Health Care Centers in Beech Grove.

“We’ll go through five or six ethical cases a week,” Father Mannion said. “It’s become complex because of modern technology, the use of respirators and family dynamics—family being all over the country instead of being centered around mother and father.”

He mentioned the case of a mother of nine children who was in the hospital’s intensive care unit.

“None of the nine children could or would agree on what was appropriate care for the mother,” he said. “It’s hard when you sit down nine children with all the physicians involved, and they’re not speaking to each other but they all want to do what’s best for Mom. Those become difficult, hard cases.”

It’s even more emotional when a case involves your own mother, a situation faced by Father Mannion and his siblings.

“I took care of my Mom for two years,” the priest said. “She had congestive heart failure. She was on a respirator for 28 days. I was one of five children. All five couldn’t agree as far as the respirator. It came down to, ‘At what point is enough enough?’

“She wanted to live, but she couldn’t live the way she wanted because she was respirator-dependent. Twenty-eight days of the siblings going back-and-forth, back-and-forth, sharpened my intuitiveness enough to say, ‘Enough is enough.’ After 28 days, we decided to remove her from the respirator.”

In such cases, Father Mannion said he is guided by three influences: prayer, help from the Holy Spirit and his education in ethics from workshops, seminars and case studies.

Similar cases challenge Gramelspacher, a medical ethicist who directs the palliative care program at Wishard Health Services in Indianapolis. Palliative care involves relieving or soothing the symptoms of a disease without affecting a cure.

“It’s not a mystery that we’re going to die,” said Gramelspacher, a 1975 graduate of the University of Notre Dame. “Given that knowledge, why do we do so poorly taking care of dying people?”

He noted that 56 million people die each year in the world, including about 2.5 million Americans. In the United States, the average age of death is 77.2 years.

He also noted that about 33 percent of American deaths each year are caused by heart disease, 25 percent by cancer and 7 percent by stroke.

Perhaps his most revealing statistics are connected to how people want to die.

“Eighty percent of people say they want to die at home, yet 80 percent die in hospitals and nursing homes,” he said. “This country isn’t a very good place to die at home, surrounded by friends and family, with your symptoms under control.”

Part of the problem, he believes, is that medical technology makes it possible to keep people alive at all costs—and often at exorbitant costs.

“There’s a technological imperative, an economic incentive to keep pushing on. Our healthcare system has to get better at managing this aspect,” he said. “As you get closer to dying, the medical issues get smaller and smaller. The priest is more important to the patient who is dying than the doctor.”

His approach to treating dying people is similar to another directive from the bishops, which states: “Patients should be kept as free of pain as possible so that they may die comfortably and with dignity, and in the place where they wish to die.”

Gramelspacher draws some professional comfort from knowing that “the whole movement of hospice and palliative care is growing.”

He also draws some personal comfort when he recalls the death of his father, Robert, on Jan. 7.

“He had a big stroke in October,” he said. “He knew he was dying. He knew he was in a nursing home, but he didn’t like it. All four of his kids were with him when he died. We had two air mattresses, a couch and a recliner in the room. I asked the nurses to make enough room in his bed so someone could lay down with him.”

Gramelspacher paused before he added, “I was in bed with him when he died. His spirit left him when he stopped breathing.”

For Gramelspacher, it was another reminder of how dignity in death should be considered as important as dignity in life.

“Why can’t the end of life,” he asked, “be as beautiful as the beginning of life?” †